Newest OS – Option-⌘-R. This option will be the newest or latest version of macOS that can be installed on your Mac. Shipping OS (Oldest OS Available) – Shift-Option-⌘-R. The “Shipping OS Version” is the macOS version that your Mac originally shipped with from the factory. This is the IR Version that you will see if you use Shift. “World’s fastest browser,” “industry-leading battery life,” and “loads frequently visited sites an average of 50 percent faster than Chrome”: Testing conducted by Apple in October 2020 on production 1.4GHz quad-core Intel Core i5-based 13-inch MacBook Pro systems with 8GB RAM, 256GB SSD, and prerelease macOS Big Sur. Battery life tested with display brightness set to 12 clicks from bottom or 75 percent. Support Ending on December 1, 2020. Apple released macOS Big Sur 11 on November 12, 2020. In keeping with Apple's release cycle, Apple will stop releasing new security updates for macOS High Sierra 10.13 following its full release of macOS Big Sur.

On May 6, 2002, Steve Jobs opened WWDC with a funeral for Classic Mac OS:

Yesterday, 18 years later, OS X finally reached its own end of the road: the next version of macOS is not 10.16, but 11.0.

There was no funeral.

The OS X Family Tree

OS X has one of the most fascinating family trees in technology; to understand its significance requires understanding each of its forebearers.

Unix: Unix does refer to a specific operating system that originated in AT&T’s Bell Labs (the copyrights of which are owned by Novell), but thanks to a settlement with the U.S. government (that was widely criticized for going easy on the telecoms giant), Unix was widely-licensed to universities in particular. One of the most popular variants that resulted was the Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD), developed at the University of California, Berkeley.

What all of the variations of Unix had in common was the Unix Philosophy; the Bell System Technical Journal explained in 1978:

A number of maxims have gained currency among the builders and users of the Unix system to explain and promote its characteristic style:

- Make each program do one thing well. To do a new job, build afresh rather than complicate old programs by adding new “features”.

- Expect the output of every program to become the input to another, as yet unknown, program. Don’t clutter output with extraneous information. Avoid stringently columnar or binary input formats. Don’t insist on interactive input.

- Design and build software, even operating systems, to be tried early, ideally within weeks. Don’t hesitate to throw away the clumsy parts and rebuild them.

- Use tools in preference to unskilled help to lighten a programming task, even if you have to detour to build the tools and expect to throw some of them out after you’ve finished using them.

[…]

The Unix operating system, the C programming language, and the many tools and techniques developed in this environment are finding extensive use within the Bell System and at universities, government laboratories, and other commercial installations. The style of computing encouraged by this environment is influencing a new generation of programmers and system designers. This, perhaps, is the most exciting part of the Unix story, for the increased productivity fostered by a friendly environment and quality tools is essential to meet every-increasing demands for software.

Today you can still run nearly any Unix program on macOS, but particularly with some of the security changes made in Catalina, you are liable to run into permissions issues, particularly when it comes to seamlessly linking programs together.

Mach: Mach was a microkernel developed at Carnegie Mellon University; the concept of a microkernel is to run the smallest amount of software necessary for the core functionality of an operating system in the most privileged mode, and put all other functionality into less privileged modes. OS X doesn’t have a true microkernel — the BSD subsystem runs in the same privileged mode, for performance reasons — but the modular structure of a microkernel-type design makes it easier to port to different processor architectures, or remove operating system functionality that is not needed for different types of devices (there is, of course, lots of other work that goes into a porting a modern operating system; this is a dramatic simplification).

More generally, the spirit of a microkernel — a small centralized piece of software passing messages between different components — is how modern computers, particularly mobile devices, are architected: multiple specialized chips doing discrete tasks under the direction of an operating system organizing it all.

Xerox: The story of Steve Jobs’ visiting Xerox is as mistaken as it is well-known; the Xerox Alto and its groundbreaking mouse-driven graphical user interface was well-known around Silicon Valley, thanks to the thousands of demos the Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) did and the papers it had published. PARC’s problem is that Xerox cared more about making money from copy machines than in figuring out how to bring the Alto to market.

That doesn’t change just how much of an inspiration the Alto was to Jobs in particular: after the visit he pushed the Lisa computer to have a graphical user interface, and it was why he took over the Macintosh project, determined to make an inexpensive computer that was far easier to use than anything that had come before it.

Apple: The Macintosh was not the first Apple computer: that was the Apple I, and then the iconic Apple II. What made the Apple II unique was its explicit focus on consumers, not businesses; interestingly, what made the Apple II successful was VisiCalc, the first spreadsheet application, which is to say that the Apple II sold primarily to businesses. Still, the truth is that Apple has been a consumer company from the very beginning.

This is why the Mac is best thought of as the child of Apple and Xerox: Apple understood consumers and wanted to sell products to them, and Xerox provided the inspiration for what those products should look like.

It was NeXTSTEP, meanwhile, that was the child of Unix and Mach: an extremely modular design, from its own architecture to its focus on object-oriented programming and its inclusion of different “kits” that were easy to fit together to create new programs.

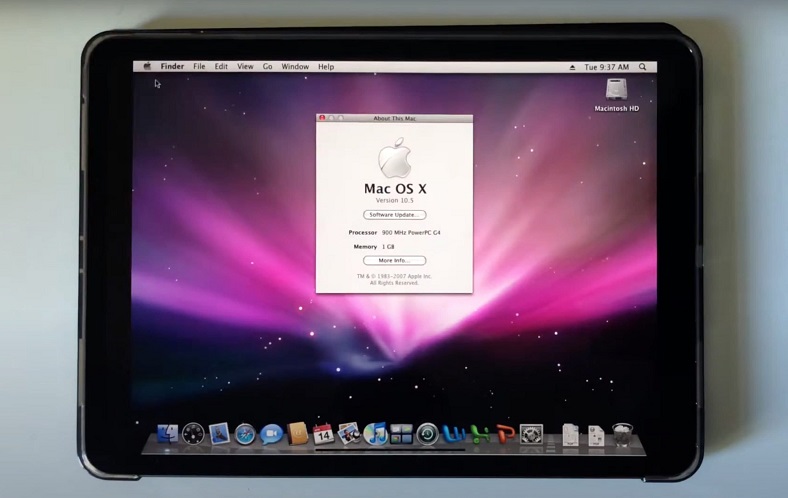

And so we arrive at OS X, the child of the classic Macintosh OS and NeXTSTEP. The best way to think about OS X is that it took the consumer focus and interface paradigms of the Macintosh and layered them on top of NeXTSTEP’s technology. In other words, the Unix side of the family was the defining feature of OS X.

Return of the Mac

In 2005 Paul Graham wrote an essay entitled Return of the Mac explaining why it was that developers were returning to Apple for the first time since the 1980s:

All the best hackers I know are gradually switching to Macs. My friend Robert said his whole research group at MIT recently bought themselves Powerbooks. These guys are not the graphic designers and grandmas who were buying Macs at Apple’s low point in the mid 1990s. They’re about as hardcore OS hackers as you can get.

The reason, of course, is OS X. Powerbooks are beautifully designed and run FreeBSD. What more do you need to know?

Graham argued that hackers were a leading indicator, which is why he advised his dad to buy Apple stock:

If you want to know what ordinary people will be doing with computers in ten years, just walk around the CS department at a good university. Whatever they’re doing, you’ll be doing.

In the matter of “platforms” this tendency is even more pronounced, because novel software originates with great hackers, and they tend to write it first for whatever computer they personally use. And software sells hardware. Many if not most of the initial sales of the Apple II came from people who bought one to run VisiCalc. And why did Bricklin and Frankston write VisiCalc for the Apple II? Because they personally liked it. They could have chosen any machine to make into a star.

If you want to attract hackers to write software that will sell your hardware, you have to make it something that they themselves use. It’s not enough to make it “open.” It has to be open and good. And open and good is what Macs are again, finally.

What is interesting is that Graham’s stock call could not have been more prescient: Apple’s stock closed at $5.15 on March 31, 2005, and $358.87 yesterday;1 the primary driver of that increase, though, was not the Mac, but rather the iPhone.

The iOS Sibling

If one were to add iOS to the family tree I illustrated above, most would put it under Mac OS X; I think, though, iOS is best understood as another child of Classic Mac and NeXT, but this time the resemblance is to the Apple side of the family. Or to put it another way, while the Mac was the perfect machine for “hackers”, to use Graham’s term, the iPhone was one of the purest expressions of Apple’s focus on consumers.

The iPhone, as Steve Jobs declared at its unveiling in 2007, runs OS X, but it was certainly not Mac OS X: it ran the same XNU kernel, and most of the same subsystem (with some new additions to support things like cellular capability), but it had a completely new interface. That interface, notably, did not include a terminal; you could not run arbitrary Unix programs.2 That new interface, though, was far more accessible to regular users.

What is more notable is that the iPhone gave up parts of the Unix Philosophy as well: applications all ran in individual sandboxes, which meant that they could not access the data of other applications or of the operating system. This was great for security, and is the primary reason why iOS doesn’t suffer from malware and apps that drag the entire system into a morass, but one certainly couldn’t “expect the output of every program to become the input to another”; until sharing extensions were added in iOS 8 programs couldn’t share data with each other at all, and even now it is tightly regulated.

At the same time, the App Store made principle one — “make each program do one thing well” — accessible to normal consumers. Whatever possible use case you could imagine for a computer that was always with you, well, “There’s an App for That”:

Consumers didn’t care that these apps couldn’t talk to each other: they were simply happy they existed, and that they could download as many as they wanted without worrying about bad things happening to their phone — or to them. While sandboxing protected the operating system, the fact that every app was reviewed by Apple weeded out apps that didn’t work, or worse, tried to scam end users.

This ended up being good for developers, at least from a business point-of-view: sure, the degree to which the iPhone was locked down grated on many, but Apple’s approach created millions of new customers that never existed for the Mac; the fact it was closed and good was a benefit for everyone.

macOS 11.0

What is striking about macOS 11.0 is the degree to which is feels more like a son of iOS than the sibling that Mac OS X was:

- macOS 11.0 runs on ARM, just like iOS; in fact the Developer Transition Kit that Apple is making available to developers has the same A12Z chip as the iPad Pro.

- macOS 11.0 has a user interface overhaul that not only appears to be heavily inspired by iOS, but also seems geared for touch.

- macOS 11.0 attempts to acquire developers not primarily by being open and good, but by being easy and good enough.

The seeds for this last point were planted last year with Catalyst, which made it easier to port iPad apps to the Mac; with macOS 11.0, at least the version which will run on ARM, Apple isn’t even requiring a recompile: iOS apps will simply run on macOS 11.0, and they will be in the Mac App Store by default (developers can opt-out).

In this way Apple is using their most powerful point of leverage — all of those iPhone consumers, which compel developers to build apps for the iPhone, Apple’s rules notwithstanding — to address what the company perceives as a weakness: the paucity of apps in the Mac App Store.

Is the lack of Mac App Store apps really a weakness, though? When I consider the apps that I use regularly on the Mac, a huge number of them are not available in the Mac App Store, not because the developers are protesting Apple’s 30% cut of sales, but simply because they would not work given the limitations Apple puts on apps in the Mac App Store.

The primary limitation, notably, is the same sandboxing technology that made iOS so trustworthy; that trustworthiness has always come with a cost, which is the ability to build tools that do things that “lighten a task”, to use the words from the Unix Philosophy, even if the means to do so opens the door to more nefarious ends.

Fortunately macOS 11.0 preserves its NeXTSTEP heritage: non-Mac App Store apps are still allowed, for better (new use cases constrained only by imagination and permissions dialogs) and worse (access to other apps and your files). What is notable is that this was even a concern: Apple’s recent moves on iOS, particularly around requiring in-app purchase for SaaS apps, feel like a drift towards Xerox, a company that was so obsessed with making money it ignored that it was giving demos of the future to its competitors; one wondered if the obsession would filter down to the Mac.

For now the answer is no, and that is a reason for optimism: an open platform on top of the tremendous hardware innovation being driven by the iPhone sounds amazing. Moreover, one can argue (hope?) it is a more reliable driver of future growth than squeezing every last penny out of the greenfield created by the iPhone. At a minimum, leaving open the possibility of entirely new things leaves far more future optionality than drawing the strings every more tightly as on iOS. OS X’s legacy lives, for now.

I wrote a follow-up to this article in this Daily Update.

Current Mac Os Version 2020

Yes, this incorporates Apple’s 7:1 stock split ↩

Unless you jailbroke your phone ↩